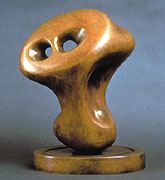

Reclining Mother and Child Sculpture Made by Henry Moore in Dallas Museum Art

The first U.Due south. retrospective of the work of Henry Moore in virtually 20 years opened at the Dallas Museum of Art this bound. The exhibition will travel to the California Palace of the Legion of Award, San Francisco, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, later this year. "Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century" examines Moore's contribution to 20th-century sculpture through 207 works spanning the entirety of his sixty-year career. It places special emphasis on his early works, exploring his role equally a carver and his dialogue with Surrealism and early on abstract fine art, as well as his impact on popular notions of sculpture in public places.

Just every bit Shakespeare evolved what Peter Brook calls "density," a narrative significant overlaid with a huge range of associations, and so too Henry Moore provides a basic meaning, but beneath it lies a dumbo web of imagistic resonances. Good theater shows the surface of life, but great theater shows what is subconscious underneath, just as expert sculpture provides us with surface involvement, only keen sculpture penetrates into and under life's gleaming formalistic surfaces to explore the meaning of the activity we apprehend as "Life."

Moore once commented that "there are universal shapes to which anybody is subconsciously conditioned and to which they can reply if their witting control does not shut them off." Herbert Read suggested that in Moore'south experience there existed "a buried treasury of universal shapes which are humanly significant, and that the creative person may recognize such shapes in natural objects and base his work equally a sculptor on the forms they suggest."i This fits neatly with the Jungian idea of the collective unconscious and, for that affair, with Roger Fry's somewhat Jungian notion of "significant course"; nosotros know that Moore was hugely influenced by Fry, in particular by his volume Vision and Design.

Moore himself referred to the viewer of sculpture as someone who needed simply to "feel shape simply as shape, not as clarification or reminiscence," and he noted agreeably that Brancusi had fabricated the 20th century conscious of shape by stripping away and refining grade to simple or closed-course shapes. But he himself, never 1 to worry about contradictions, did exactly the reverse past opening upwards shapes and by combining them. How can i conceivably use the repeated themes of mother and child, reclining figure, and seated figure, all of which have long lineages of association, emotion, and thus "description or reminiscence," yet claim that ane is seeking unproblematic class?

Critics have tended to underestimate Moore'due south contradictions and complexity.Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross(1955–56) is a crucifixion scene with, every bit Margaret Garlake observes, "allusions to a man torso, with truncated limbs and facial features…reduced to a gaping orifice."2 She notes that the critic Susan Compton suggested Francis Bacon'due south Three Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion as a determinative influence, merely then concludes that Moore'due south work "tin more convincingly be located within a pastoral and holistic reading of nature than in the existentially orientated context of Bacon'south painting."iii Much has been fabricated of Moore'south interest in landscape, in particular the mural "readings" often discerned in the reclining figures, but to suggest "a pastoral and holistic reading of nature" is to ignore huge swathes of Moore's oeuvre and to be recumbent before accepted notions (promulgated past Moore and his proselytizers) of humanistic, untroubled surfaces displaying a warmly maternal, kindly tenderness.

In fact, there is a Lawrentian sexual aspect to Moore (a deeply troubled psychological aspect in which repressed aspects of personality ooze out through works such as Upright Motif), which makes the proffer of Salary's influence all the more probable. (There is a corollary here with Giacometti's influence, noted by John Russell, in terms of sexuality). One does not need an "existentially orientated context" such as Bacon possibly possessed: the bespeak of kinship lies in the darker impulses of the psyche that are given expression, overtly in Salary but for the most role covertly in Moore.

Adrian Tinniswood notes another oversimplification, that Moore's coal mining "background led generations of art critics to make heavy-handed comparisons betwixt cut into rock at the coal face and creating sculptures."4 This is a misunderstanding on ii fronts. It overestimates his mining background (his male parent was a miner for merely a short menstruation earlier condign a mining engineer—quite unlike from working manually at the coal confront); it also underestimates the formative influence, not just of local and family tradition, but more importantly, of childhood images. Moore was just "downwards the pit" as an observer in the 1940s, at the asking of Kenneth Clark—and it was not an enjoyable experience for him. While Moore undoubtedly heard stories from his grandfather and father, it was a disused quarry in which he played as a child, not a disused coal mine. And a quarry is a rich source of images, textures, and sensations for a sculptor-to-exist.

Moore once compared the Davids of Michelangelo and Pisano, considering that the Pisano "had backside it an intensity of human understanding, of deep personality," which "had all the implications of the contradictions, troubles, and worries inside its caput that Hamlet had, whereas the Michelangelo had no existent troubles in its head at all, no unconquerable problems."5 These comments are very revealing on a number of levels. The references to Shakespeare, and his comment that Pisano was a great sculptor considering he used "three-dimensional forms to affect people, to portray man feelings, [and] to express great truths," indicate that Moore'south ultimate goal was the combination of feeling or emotion and great truths or themes, every bit in a Shakespearean play. He was likewise, by implication, reacting against sheer physical skill (Michelangelo) in favor of content (Pisano), much as one might compare Ben Jonson'due south carefully constructed plays with Shakespeare's baggier, less shapely, but more powerfully explored and emotive plays.

In add-on, the reference to Hamlet, a man who had marked bug of an emotional and sexual nature with his mother, is perchance revealing in terms of Moore's expression of his "contradictions" and "emotional wellsprings." Moore himself, discussing tactile experience, noted that every bit a boy he massaged his female parent'south back. He then suggested that while working onSeated Woman(1957) he institute that he was "unconsciously giving to its dorsum the long-forgotten shape of the i that I had so often rubbed equally a boy."6 The implication is that his "long-forgotten" experience in relation to a woman "no longer so very young" just re-emerged in 1957. This scarcely squares with the interview that Moore gave Herbert Read in 1977 in which we are told that this rite was performed two or three times a calendar week for a menses and that he never forgot the awareness of her flesh and basic, the flesh yielding, and the bones resistant beneath kneading fingers.7 Moore'south biographer Roger Berthould acknowledged the "Oedipal overtones" that "doubtless played no minor part in shaping his preoccupation with the female figure equally a theme."eight

Moore's mother, described by one of her grandchildren as "a very handsome woman…[who] had the kind of dignity that Henry'south figures accept," was for him "absolutely feminine, womanly, motherly…I suppose I've got a mother circuitous."ix Vi years subsequently, afterwards agreeing that the women in his sculptures "showed them to be in command," Moore told John Heilpern that his mother was "accented stability" for him, so much so that he would be "terrified she wouldn't return. So it's not surprising that the kind of women I've done in sculpture are mature women rather than young."x

In a letter to a friend in the '20s, most a wealthy common acquaintance, Moore wrote that if he were in the latter's position he would go to a country district and expect until he "found and wedded one of those richly formed, big-limbed, fresh-faced, pedigree state wenches, built for breeding, honest, simple-minded, practical, common-sensed, healthily-sexed lasses that I've seen most here."11 This description fits his female parent, who produced eight children, remarkably well. If it doesn't exactly fit his wife at the time of his union (a witting try to interruption away from the template?), it does signal that his preference for generously proportioned female bodies was more than just an interest in formal considerations.

A psychologist would appreciate another strand in Moore's piece of work, the utilize of what we now recognize equally classic science-fiction imagery, influenced past Surrealism. Science fiction has always been a medium of displaced anxiety, in which earth-bound scenarios, often in relation to sexuality, are transmuted into frightening images or metaphors. In the motion picture Conflicting, for case, the most nightmarish attribute is the transposed sexuality: those fearfulness-inducing creatures, virtually unstoppable predators, have enormous mouths whose dripping fangs exist within a visual representation of the vagina. Moore's surrealHelmet (1939) is, in some means, an eerie anticipation of this kind of science-fiction imagery (and specifically of the alien young breeding in the laboratory of the human body), with its sinuous, glossy vaginal cavity containing or incubating a biomorphic humanoid.

The "Helmet Heads" serial, includingUpright Motive No. 8 (1955–56) with its swelling biomorphic forms,Rex and Queen(1952–53) with its insect-similar imprint upon the human figure, andThree Slice Vertebrae (1968) with its virtually sticky biomorphism (rounded breast and socket shapes budding, sliding, distending, inflating, and stretching in a paradigm of sexual ambivalence), provides evidence of Moore's continual deployment of images of feet that anticipate science fiction. A brutal case-in-point is the Maquette for Mother and Child (1952), which would be perfectly at home if placed within the early work of the immature British sculptors dubbed The Geometry of Fearfulness generation, a group that included Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick, and Bernard Meadows, Moore's banana of the flow, who produced spiky, jagged, disturbing images.

Maquette shows us 2 "scientific discipline fiction" figures, the "child" seemingly almost to bite off its mother's breast. Moore quaintly and disingenuously suggested that the baby was just gnawing, merely its rima oris is distended to such an extent that information technology is as large as the entire breast. David Cohen, the critic who wrote the entry for this work in Celebrating Moore, notes the "terrible struggle" in the work between female parent and child. Citing Erich Neumann's Jungian theory that the mother figure represented the "terrible" mother, archetype of Tantalus, Cohen then refers to Herbert Read'southward relating of the epitome to the theories of Melanie Klein, a psychoanalyst inside the Freudian fold whose theory included a notion of fixation on the "fractional object" such equally the chest.

However, as Cohen further notes, Alan Wilkinson, ex-curator of the Moore Centre at Ontario, dismisses such notions, preferring instead to run across the sculpture, on the basis of a link between a drawing in Moore'due south sketchbooks and an illustration in a book he owned, equally deriving from a Peruvian pot.12 This information, all the same, does not invalidate whatsoever psychological or critical exploration. Sources are only interesting in terms of what an artist makes of them. Moore's science-fiction imagery and his recurring depiction of seemingly maternal or earth-goddess images, with their biomorphic ambiguities and atavistic anxieties, are evidence of a covert and fiercely repressed dark sexuality.

As recently as 1998, Anita Feldman Bennet took the usual disquisitional view of Moore's association with the Surrealists in the 1930s, regarding information technology as tentative.13 She acknowledges, withal, that Surrealist concepts such as metamorphosis and transformation "informed his work throughout his career." The link between Moore and Surrealism centers on psychoanalysis and its various interests: the unconscious, the ambiguity of certain kinds of imagery, the juxtaposition of objects, various kinds of associations, babyhood, and dreams. Moore oft skillful a form of automatism in his drawing. He conspicuously responded to the Surrealist do of using rocks, bones, or other natural objects as the footing for transformation. Compton even suggested an early date for this exercise, arguing, quite logically, that in the wake of Moore'sComposition (1931), the sculptor "began systematically to transform pebbles and bones into figures under the influence of the Surrealists."14

While Moore's do suggests that the complex aspects of Surrealism appealed to him—those areas that delight in ambiguity, association, and proposition—critical reaction tries to interpret his work either past sidelining the importance of Surrealism or by developing simplistic notions of eternal women or primal beings—generic types whose largesse is illustrational, depicting some general notion of what it means to be human. The irony is that Moore'southward all-time work is quite the opposite: information technology is highly specific, highly imaginative, highly charged with personal complexity, and highly influenced past Surrealist exercise. This, of grade, does non end whatever given work from having archetypal implications. Simply Moore is rather more the sum of his generalities.

Moore noted that "the work of art with what might be chosen prophetic vision is doing more than for fine art than the public authority that plays for condom and gives the public what the public does not object to."15 The irony hither is that Moore was, and even so is, frequently perceived as someone who watered down Modernism and thus played for safety, giving the public what it didn't object to. This is partly true. Moore colluded in this strategy when he turned out huge numbers of works, frequently in varying sizes, that could exist placed nearly anywhere.

Moore was lucky on at least three counts. First, he arrived in the wake of Epstein who, to quote Penelope Curtis, had "taken the brunt of the press's attack on emergent modern sculpture." 2d, he was fortunate in his friendships with critics, curators, and museum and gallery directors of major importance (non merely Roger Fry, Herbert Read, and Kenneth Clark but also Adrian Stokes, William Rothenstein, and Sir Philip Hendy, Clark's successor at London's National Gallery). Finally, Moore was historically blessed, in that abstraction was specifically counterpointed by Social Realism during the Cold War period. Compared with the art of the Soviet Bloc, and because of Moore'due south association with the abstractions of Barbara Hepworth, Moore'due south piece of work could be seen equally primarily open up, free, and humanistic; information technology was considered non-political, non-threatening, and essentially devoid of anything other than elementary uncontentious subject area thing—a viewpoint through which the promoters could nudge viewers into seeing what they wanted them to see.

Thus Moore (and to a sure extent Hepworth) were toured globe-wide by the British Council, to a degree that seems well-nigh impossible today. Moore himself, as Margaret Garlake points out, was the most heavily promoted British creative person of the century. This state of affairs was, and nevertheless is, cultural politics with a vengeance. Moore became a household name, an international star like Picasso. In some senses Moore paid a price (albeit willingly) for this amazing platform of support. The polite fiction finer stating that his work lacks specific, substantial subject matter not only allowed the British, and in item the British Council, to develop him every bit the ideal propaganda subject, just also, I suspect, led to a lack of critical scrutiny of the sculptor's work that continues today.

But Moore (just like Picasso) did dictate the terms in which he was discussed, aided by item social and political climates. He was astute enough to change his heed, slowly, when convenient. Past 1951 this champion of direct carving could claim that the method "is important, simply should not be a criterion of the value of the work," a very handy position for a sculptor who was producing very little straight carving, opting instead for mass production of bronzes.16

There is general agreement among many critics that Moore's piece of work suffered after the war, when he effectively jettisoned direct carving and began to movement into large-scale product of bronzes. The virtually factory-similar product (requiring studio methods not much dissimilar from those of a 19th-century sculptor in which assistants were used in stone piece of work equally well as bronze), reinforced by the more overt figuration, not only increased Moore's popularity amid the general public, but also possibly created the climate of critical opinion which saw Moore'south postwar piece of work equally evidence of a slackening of aesthetic rigor.

And indeed there are problems with many of Moore's postwar works: the sharp jettisoning of the "truth-to-materials" artful took time to resolve itself in terms of the new work; the mill-manner studio weather led to over-product, to generalized (rather than individualized) works that lack sensitivity to surface and governing idea; and, in some cases, in that location are serious questions about the scale of the works and nature of the participation of some of Moore'due south administration.

But that having been said, in the postwar menses, Moore began to become into his pace in terms of balancing form and content. Formally, he began to find an equipoise between his huge range of contradictory impulses. His collection of yin and yang aspects now encompassed tradition versus innovation, the subterranean versus the surface, the abstract versus the figurative, the harmonic versus the expressive, form versus content, naturalism versus stylization, and the passive versus the active, only to mention the nigh obvious of polarities. He now developed the vocabulary and the ways to deal with the complexities of his inner cocky. He also had the do good of a long period of gestation—the state of war years—during which the act of making sculpture itself had to accept 2d place to drawing and note-taking.

In a sense, the postwar flow was ane long exploration of his inner self, an exploration that not only allowed his sexuality to seep through, but likewise allowed it to manifest itself in all its variousness: the darkness too as the light, the fearfulness as well as the sensual pleasure, the interest in the male every bit well equally the female. The paradox was that nobody noticed, or if they did, they didn't comment publicly. Possibly, since Moore was increasingly making large-calibration public sculpture, the sheer scale interfered with the obvious—a instance of not seeing the forest for the copse.

His prewar work embraced a huge diversity of sources and styles, and the same is truthful of the postwar work: Expressionism, Neoclassicism, biomorphic Surrealism, even Cubist references are all office and parcel of the latter half of his career. The point is that pre-war or postwar, Moore went on arresting influences in a consistent manner.

Later on noting that "Moore's sculpture didn't go equally far as Arp in interpreting the human existence in terms of nature," Albert Elsen in one case remarked that the sculptor'due south thought "was then adult female-centered that this was not possible."17 Once alerted, one finds many such brief hints about Moore and the sexual impulse in his work, only they are fragmentary and illusive. Even John Russell speaks in lawmaking, referring to Moore's "readiness to let the demons loose" and suggesting that "the private Moore has kept his secrets."18 The decipherment of those secrets, I speculate, lies precisely in the expanse that Kenneth Clark said he had always wanted to talk over only could never exercise then, because of his shut relationship with Moore.19 That area is sexuality and the manner in which it manifests itself in the sculptures.

Thousands of words have been written virtually the female forms in Moore's work but virtually of them consist of formal analysis. The descriptive references are non-threatening: aristocratic, serene, static, healthy, optimistic, passive, firmly fleshed, fully rounded, introspective, contemplative, non-erotic, mature, or middle-aged, unemotional, and faceless. Moore'south women are the possessors of a quiet majesty, nigh entirely lacking in any interior or psychological life. Even when a psychological approach is fabricated, information technology stresses the generalizing element.xx One might have idea, however, that someone would have noticed the seeming paradox that in Moore's drawings, the women are, upon occasion, quite specifically immature, nubile, naked, and individualized.

With respect to Moore'south prewar work, descriptions of the women as passive are adequately apt. But they brand picayune sense when practical to the postwar sculpture, equally an exploration of the wide span of Moore'south works sited in and effectually his studio at Perry Dark-green makes clear. As John Russell noted over thirty years agone, there is still much decipherment to exist washed on the private, hidden aspects of the sculptor. His written statements on sculpture, incessantly quoted and blithely believed, are a good guide to what he was adamant to hide in his concentration on form rather than content.

If Moore, in his earlier years, had conformed with the general notion of paring away traditional associations from his fine art, he knew perfectly well that in that location was simply then far that ane could become in this direction. Elsen believes that the sculptor counted on the persistence of psychological associations with shape. This Jungian view of the universe as well explains Moore'southward traditionalism, in terms of materials and basic subject affair. New materials, whether used by the Constructivists, by the new generation of British sculptors in the '50s, or by artists everywhere afterwards the '60s, were selected for their lack of cultural retentiveness, art historical baggage, and reference. Moore needed precisely these areas excluded by the new sculpture. His art was non 1 of paring downwardly but rather, similar a pebble in the puddle, of resonance, whether in the echoing singularity of the ripple upshot or in the complex creation of meaningful ambivalence.

Brian McAvera's review ofHenry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, the catalogue of the exhibition organized past the Dallas Museum appears in this issue.

Notes

1 Herbert Read, A Concise History of Modern Sculpture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1964), pp. 177, 180.

ii Margaret Garlake, New Fine art New World: British Art in Postwar Society (New Oasis: Yale Academy Press, 1998), p. 191.

3 Ibid., p. 192.

4 Henry Moore in Public: A Pocket Guide to Works by Henry Moore in UK Public Collections (London: BBC / Henry Moore Foundation , 1998, p. seven.

v Quoted in Susan P. Compton, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue (Cracow: BWA Gallery, 1995), p. 31.

6 Quoted in Henry Moore on Sculpture, edited by Philip James (London: MacDonald, 1966), p. 131.

7 Quoted in Roger Berthould, The Life of Henry Moore (London: Faber & Faber, 1987), p. 26.

eight Ibid., p. 26.

9 Donald Hall, Henry Moore (New York: Gollancz, 1966), p. thirty.

10 Observer Magazine, Apr thirty, 1972, pp. 28–37: 37.

xi Quoted in Berthould, op. cit., p. 83.

12 David Cohen in Jubilant Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation , edited by David Mitchinson (London: Lund Humphries, 1998), p. 234.

13 Moore in Public op. cit., p. 136.

xiv Compton, op. cit., p. 27.

15 Ibid., p. 33.

16 Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue (London: Tate Gallery, 1951), p. iv.

17 Albert Elsen, Modernistic European Sculpture (New York: Braziller, 1979), p. 50.

18 Russell, Henry Moore (London: Penguin, 1973), p. 260.

nineteen In the BBC documentary, Henry Moore: Carving A Reputation, 1998.

20 Anton Ehrenzweig (quoted in Russell, op. cit., p. 260) in The Hidden Society of Art referred to the "Great Female parent," while Erich Neumann'due south The Archetypal Globe of Henry Moore (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1959, p. 17) considered that the female reclining effigy came ever closer to the archetype of "the earth goddess, nature goddess and life goddess."

Source: https://sculpturemagazine.art/the-enigma-of-henry-moore/

0 Response to "Reclining Mother and Child Sculpture Made by Henry Moore in Dallas Museum Art"

Post a Comment